Why do we prefer that logo? What colour scheme would resonate with this community? Why do we think that street is more beautiful? If you want intelligent and robust answers to these questions, then ask a semiotician.

Chris Arning is the Founder of Creative Semiotics and works for some of the world’s leading brands including Netflix, BMW, the BBC and the Estonian Government. He is a founding member of the LDN Collective and is playing a central role in many of our projects, including the Wolfson Prize award-winning submission Fast Forward: The Future of Health & Wellbeing and commissions for Hill Group and Clarion Housing Association.

Chris Arning, Creative Semiotics

“A semiotician analyses every detail of a brands ‘touch points’, of which there are many in the built environment, and to interpret what they will mean to different demographics. Because semioticians are immersed in visual and consumer culture, they can tell you why this colour is clichéd and isn’t right or how to resonate with changing culture. Place is about the elements and experiences that make a space unique – the architecture, people, smells, sights and sounds.

It is often easier to think about a place by what it is not, and all developments want to get away from being a ‘non place’ like airports and shopping malls. These are not the sort of spaces that stick in the memory, unless it’s for the wrong reasons. But we don’t just want to avoid being a non-place, we want to create coveted and liveable places that have meaning.

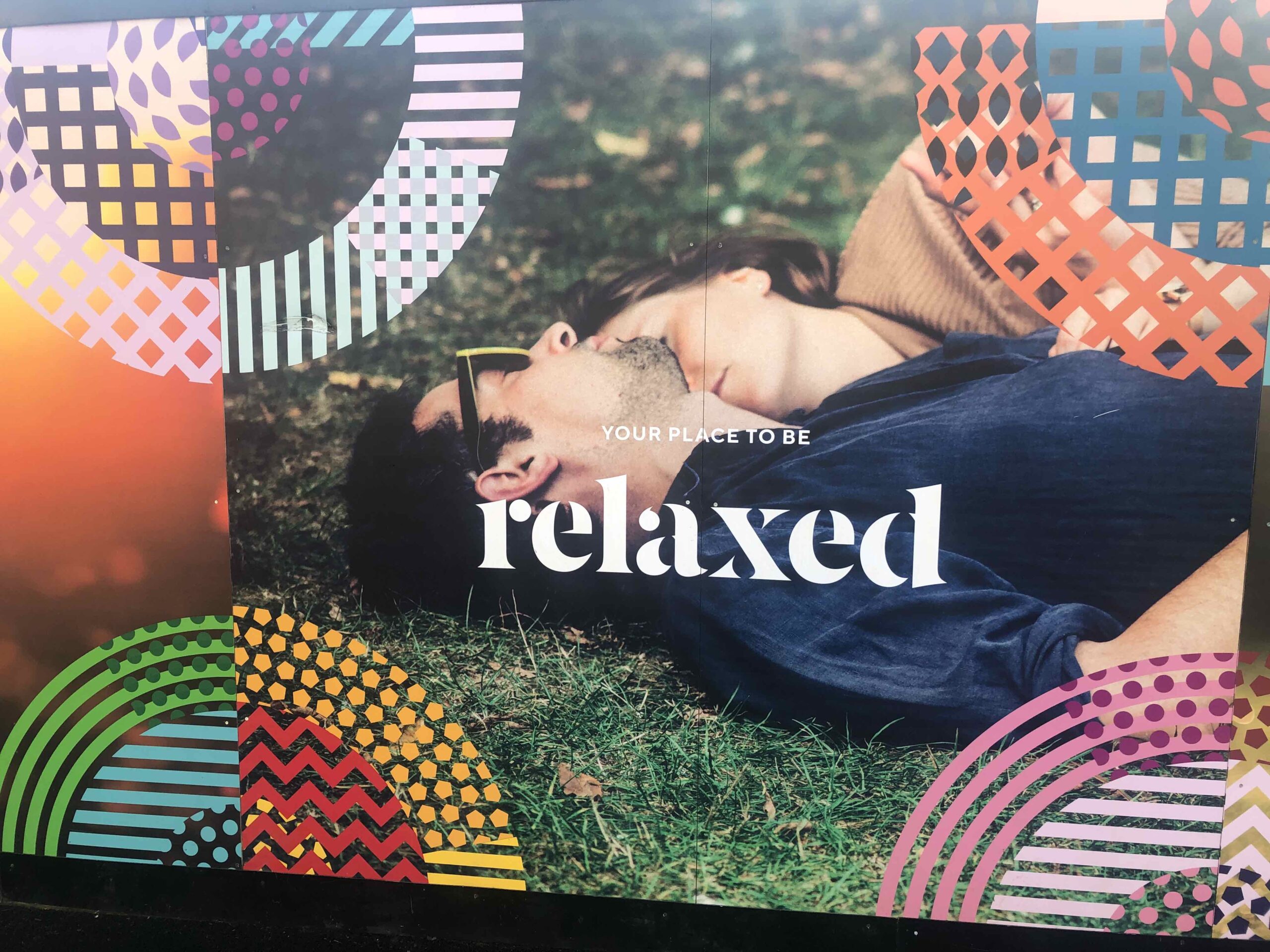

Primrose Hill - a coveted and liveable place

The word culture is bandied about as a buzzword, yet it is one of the hardest words to define. In the UK, it became synonymous with an appreciation of aesthetics and high arts, often associated with elitism and snobbery.

In recent times, it has become synonymous with sub-cultures, like internet niches. When we think about cultures, we think about different traits and how they interact. We are told Germans are direct, Japanese allusive, British too polite to be honest and Dutch too honest to be polite!

Semiotics is about codes and patterns found in different cultures which can be visual, narrative, linguistic or behavioural. British humour would be an example of a national code, or kawaii of ‘cuteness’ in Japan, but culture is complex and contains countless sub-cultures. Hip hop has its own codes of expression, visual, sound and language. Hip hop artists will talk about place in a way that is different from a local historian.

Culture is never static and semiotics studies the way it changes over time. Emerging codes are what our clients are looking for, and semiotics helps understand their meaning, for brands to stay relevant. Because semiotics is the study of meaning in culture, it closes the gap between what brand owners think they are communicating and what they are actually communicating.

At the LDN Collective, our mission is to “tackle built environment issues from every angle”. We know the need for placemaking is increasing and there is a desire to create distinctive brands for places, but the built environment is way behind the curve. As a Japanese colleague working in the hospitality sector bemoaned, branding in real estate is an afterthought.

As placemakers, we understand that a brand should be ‘baked in’ to the infrastructure of regeneration projects and not just added like glitzy and clichéd wrappers, slapped on at the last minute to sell apartments or rent office space.

Our research has shown that residential developments in the UK tend to be stereotyped into one of two camps. Either they are what we’ve termed ‘prison block chic’, with all the snobbery that entails, or they are swish developments that lack soul and are condemned by pejorative labels like ‘gentrification’. We believe that for clients to truly champion thought leadership in new developments, we need to avoid these clichés.

Naming can signal the mindset and attitude of the developer, like Fish Island or Elephant Park for example. Development names that pull in heritage elements or folklore infuse the place with the spirit of the past, through a contemporary lens.

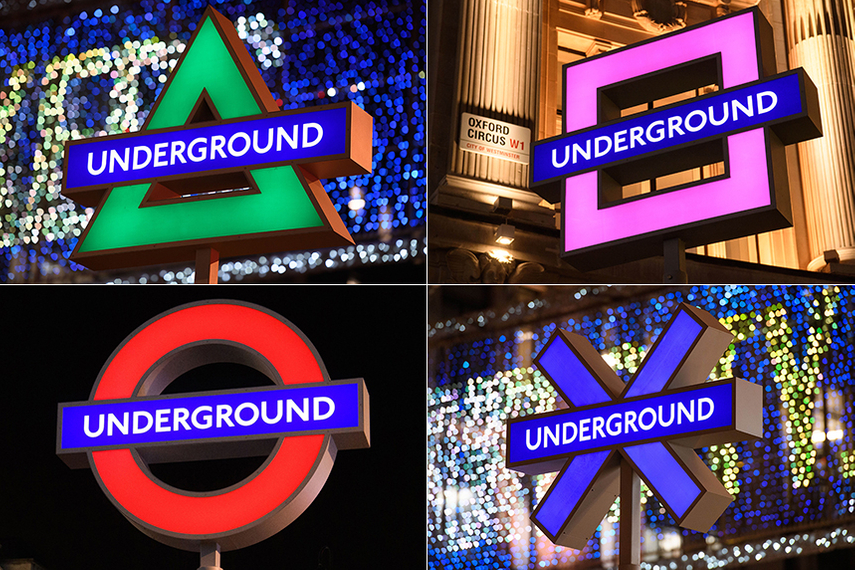

I love this example of a co-branding exercise in 2020 which shows the power of symbolism within the urban environment. PlayStation teamed up with London Underground for the launch of the PS5 and replaced the London Underground roundel with Playstation’s trademark button symbols.

There is a visual wit and ambient art feel in the juxtaposition. The fact that Playstation is embedding itself, literally, in the London skyline gives great kudos and cultural capital to the brand itself whilst London Underground benefits from the associated cachet and exposure.

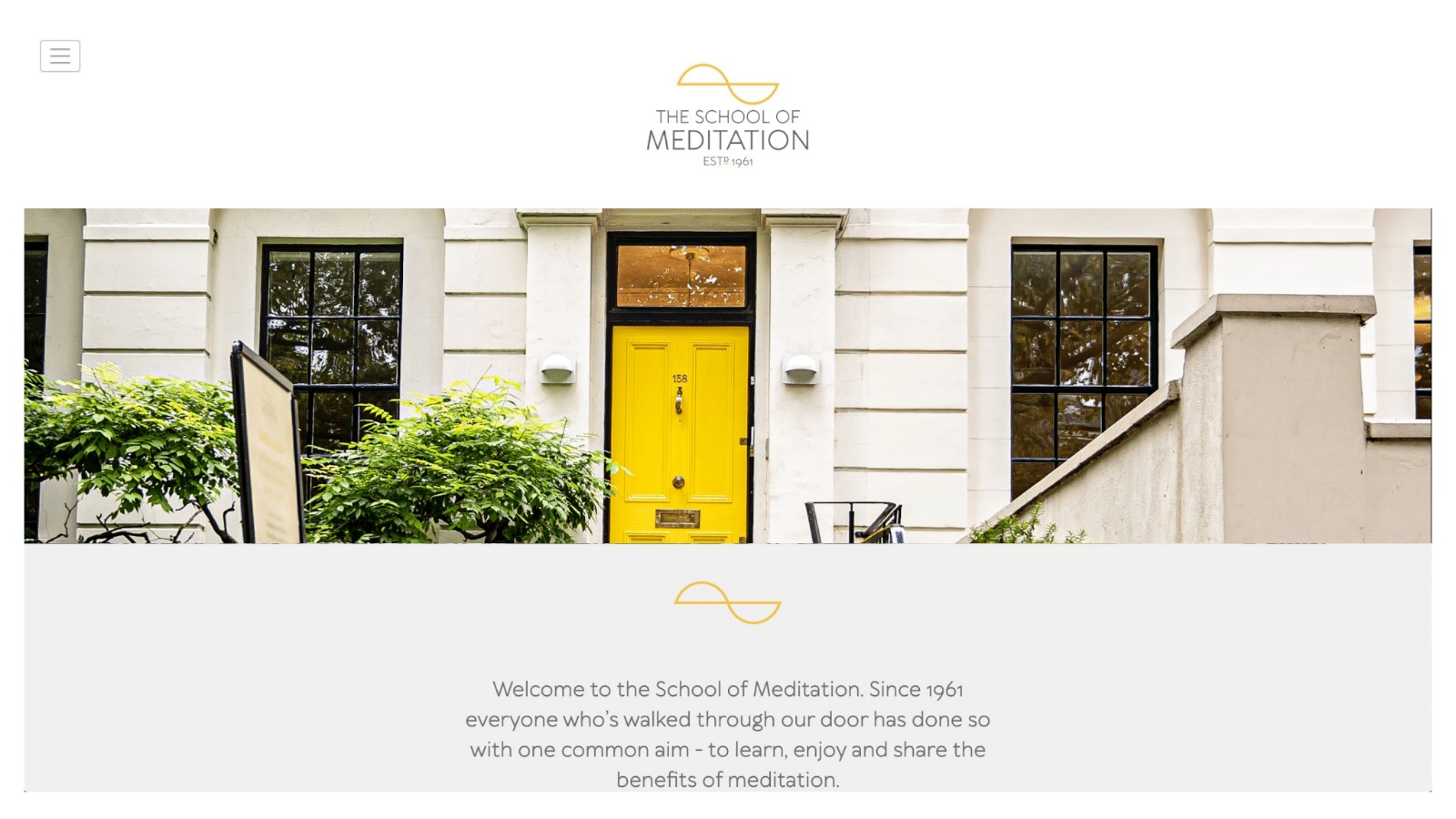

New developments bring in considerations of class and disparities of wealth, with a need to balance sales values with a sense of locality and social cohesion. Semiotics can help, with sensitivity to soft signals that convey who this place is for. Creative Semiotics did some work for the School of Meditation in West London who wanted to appeal to a wider demographic within the socio-economic and racially diverse borough of Kensington and Chelsea. We pointed out that the use of an imposing Georgian house was likely to be off-putting, as it conjured up perceptions of wealth and exclusivity. The rebrand softened the image and changed the depiction of the building, with a wider shot including more trees and windows signalling openness. By reviewing data over 6 months, a definite positive trend can be seen in the diversity of people engaging.

The Head of Marketing wrote:

“it was extremely helpful as it enabled us to form a deeper understanding of how our brand, images, premises, geographical location, and its overwhelmingly white and older membership will be experienced by people from non-white, non-British and non-affluent backgrounds.”

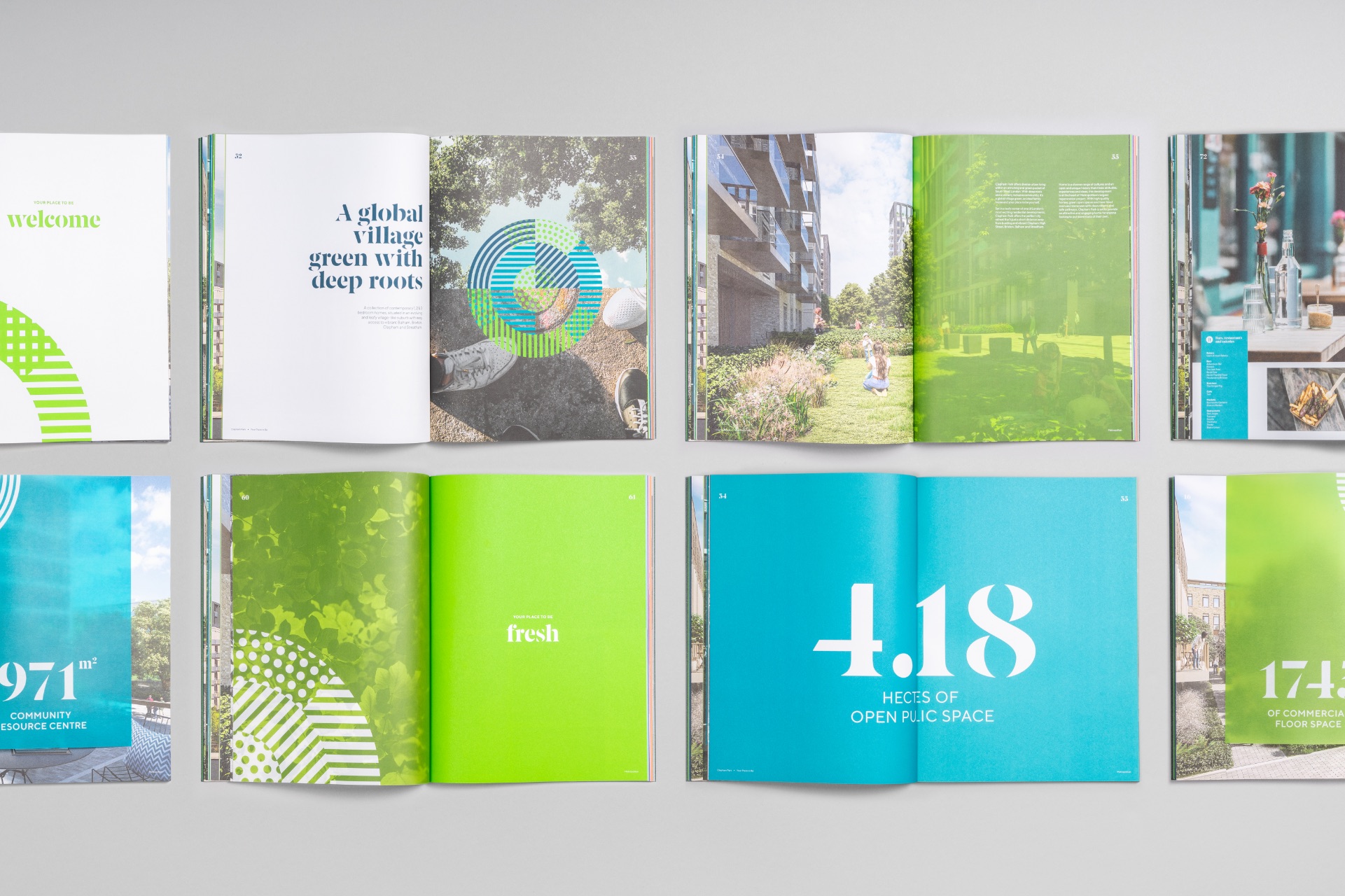

We were recently commissioned to use semiotics to support Hill Group in their bid to become a partner to MTVH for the massive Clapham Park development. We carried out a SWOT analysis of the existing branding, to show them the positives and the pitfalls. The strapline we analysed, ‘global village with deep roots’ was striving to achieve this balance, but needed to avoid cliché or euphemism to avoid cynicism.

The circular motif and benday dots are friendly and connote a positive idea of community and togetherness – so it’s a good fit for post-Covid sensibilities. But once you start to develop something that needs to take into consideration the needs of the specific local community, such a motif should be invested with more meaning so as not to appear superficial.

Clapham Park branding by Better Agency

Every time you show user imagery and cast people to appear, you influence the way your audience perceives who you are and what you stand for. In this case, when it is a mixed use and mixed tenure development, the imagery will convey socio-economic cues that will peg the price range, and perceptions of how aspirational and affordable a place will be.

Using patterning from certain cultural traditions can signal it is cosmopolitan, but can also be accused of appropriation. Working out what you want to convey and which visual elements do that best is a semiotic skill.

Clapham Park branding by Better Agency

Futurecity ran a workshop for LDN Collective members recently, which focused on the burgeoning placemaking industry, showing that many commercial interests are converging on this area but it still a ‘Wild West’ with many different definitions, paradigms and approaches. Mark Davy from Futurecity remarked “We want to have a collective position on placemaking. No one has stood back from what is going on, because it is happening so quickly and there are so many component parts.”

Nevertheless, one definition from the Urban Land Institute struck a chord; “Cultural Placemaking intentionally leverages the power of the arts, culture and creativity to serve a community’s interest, whilst driving a broader agenda for change, growth and transformation in a way that builds the character and quality of place”

Futurecity's cultural strategy for Heart of London BID

What I thought was most interesting was the increasing involvement of marketing and brand consultancies in this area, the increasing application of cultural strategy in the positioning of places, cities and destinations and how classic brand strategy is being applied. It might be said, that the intangible aspects of these new places and destinations, their cultural districts, artistic attractions, and music venues for example, boost the sense of cultural capital.

Semiotics when applied to the built environment can make more distinctive and interesting places which are celebrated by their communities. By creating frameworks and understanding how developments can have soul, uniqueness and that the communications are authentic and culturally resonant. It gives confidence to partners and stakeholders, by unifying teams around non-arbitrary creative objectives, from planning to construction, sales and marketing.”

Chris Arning as Narrator for "Fast Forward - the Future of Health & Wellbeing"

Here is a testimonial from Chris Arning, Founder at Creative Semiotics. Please do get in touch if you would like us to offer similar support.