“Good afternoon, I’m delighted and also humbled to be here today. We have heard from truly inspiring speakers and I would like to thank Arijana, Marina and colleagues from the UN Development Programme for organising such an excellent conference. My name is Max Farrell I am the Founder of The LDN Collective. We are a group of built environment experts and creatives who collaborate on projects which improve peoples lives and the planets prospects. Our members include architects, engineers and landscape designers as well as specialists in things like zero carbon, social impact and modern methods of construction. We also have film makers, graphic designers and communications experts so we describe ourselves as a ‘one stop shop’ for projects anywhere in the world.

I was fortunate enough to be the Project Leader and author of the Farrell Review of Architecture and the Built Environment, commissioned by the UK government and published 5 years ago. We made a number of recommendations, many of which have been implemented. For example, the need for every town and city to have an urban room, where people can go to understand the past, present and future of their place. The most important issue we stated at the time was climate change and the role that cities have to play, with the increasing proportion of the world’s population living in cities which are by far the biggest contributor to carbon emissions and the climate emergency that we are facing.

In the last year, COVID-19 has really accelerated change in terms of city making. There have been major shifts in the use of technology, with so many people working, learning and shopping from home, whilst rediscovering local centres, walking and cycling more and moving away from dependency on cars. One of my favourite quotes was the mayor of Bogota, who said, the sign of a developed country is not when poor people own cars. It is when rich people use public transport. And I think that is powerful and true for many reasons.

At The LDN Collective, we are tackling complex problems from multiple perspectives. For example, the future of town centres with retail in decline as well as the future of our parks and green spaces which I will talk more about and show you a short film. Our members previously masterplanned the first eco town to be built in the UK at NW Bicester which is true zero carbon – that means regulated and unregulated emissions. We are currently working on the first new town in the UK to have a response to the climate emergency in its DNA in Harrington, South Oxfordshire. As well as being zero carbon we are increasing biodiversity, addressing nitrogen in the air and water, enabling local food production and creating local mobility hubs.

It is now, more than ever, essential that towns and cities are healthy places where people can live longer and happier lives. We are working for Therme group who are creating wellbeing facilities in cities around the world, like 21st century roman baths, not just for leisure but also access to nature indoors and outdoors as well as arts and culture. Immersive experiences centred on health and wellbeing which are affordable and accessible to all.

We must encourage more active lifestyles and also ensure that cities are for everyone including different age groups, ethnicities and physical abilities. The focus on smart cities, I would argue, is too narrow. The use of data to inform decision making is important. But the most important thing about cities is their human values and how they encourage human beings to coexist in harmony with each other and with the natural world.

Human Values like kindness, tolerance and diversity are the reasons why I love London, but also the incredible creative industries and access to arts and culture, which will become even more important as we emerge from the pandemic, as a means of expressing our feelings about the traumatic experiences we have all been through, and healing through storytelling and reconnecting with each other.

I am involved in plans to make the Thames Estuary, 80 kilometres east of London along the river Thames, into the world’s most exciting cultural hub. This is large-scale, post-industrial regeneration which is driven by the creativity of the people that live and work there.

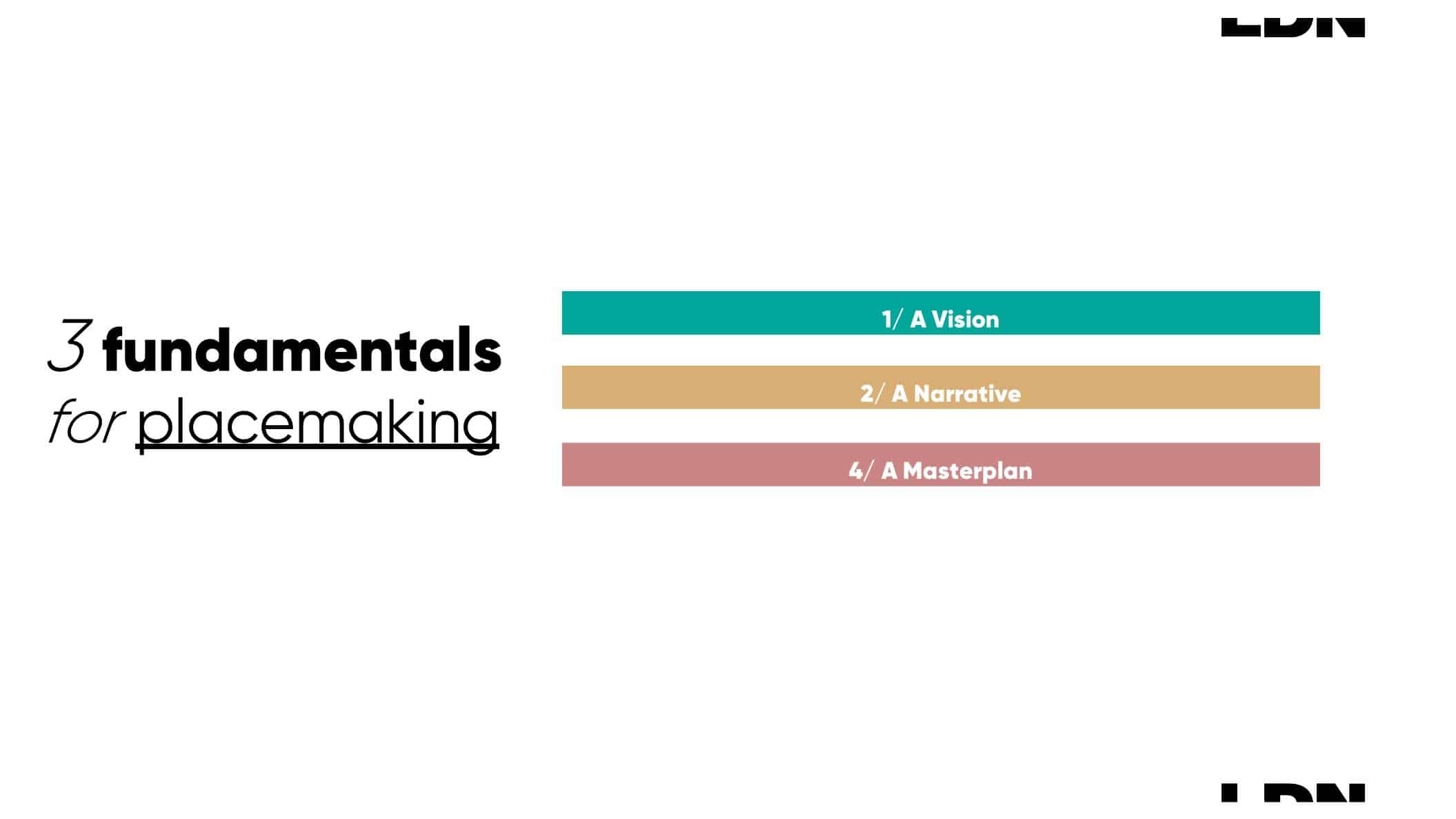

The idea today is to look at ways to help developing countries in terms of placemaking and urban planning. One of the things I’ve learned over the years is that to make change happen effectively, there are three important things that every place needs – a vision, a narrative and a masterplan. You have to start with a vision. Whatever your starting point is, and we’re all starting at different points as places are evolving and changing. Particularly, in terms of the developing countries that are dealing with post industrialization, poor quality housing and infrastructure, you need to start with a vision. That is the most crucial role of leadership, in fact, the vision itself can lead.

It is also the foundation of good placemaking. Quite often, the starting point is current regulations and policies, and that is actually the wrong place to start, working back from what we can and can’t do today, what we should be doing is thinking where do we want to be in 5, 10, 20 years time. This will influence and shape public policy and investment decisions by setting out principles that you want to adhere to.

With placemaking, there are fundamental principles which are true wherever you are in the world. Focus on mixed use, the public realm, walkability, the human scale and now more than ever, on environmental impact as well as social impact. How can placemaking tackle climate change and the biodiversity crisis whilst also addressing structural inequalities relating to race, gender, class and physical abilities improving social mobility and opportunities for all?

The second element involved in creating a vision that is compelling and drives change is to have a clear narrative, a narrative for change. Every place has a story to tell but that story is not just what happened over the last few hundred years. It’s actually what is happening today and what direction things are heading in based on a deep understanding of what has happened in the past. By creating a strong narrative that is clearly understood by everyone, including school children which should be the real test, it can help drive change. It can change the very nature of a place and it’s prospects.

The third element needed is a masterplan. There is often a misconception that a masterplan is a fixed design framework, that should not be the case. A good masterplan is based on sound principles, but allows for change, and the ability to respond to socio-economic circumstances.

A city can have a masterplan which is more like a strategic framework identifying locations for growth and improved connectivity and social infrastructure. But the key thing is, it will be a spatial plan. It will look at, shape, form, and types of uses. Regional planning is not as common as it should be. Whether you are in developed or developing countries. However, it is essential. Without a plan, we don’t know where we’re going. If we don’t know where we’re going, we can’t say where we will end up.

I know I’m running out of time, so I would like to show you a short film about an initiative called #ParkPower which we started last summer, in the middle of the first lockdown. It is a collaborative vision for the future of our parks and green spaces.

We used the Commonplace engagement platform to ask Londoners what they valued about their green spaces, and their ideas for the future. As a multidisciplinary group, The LDN Collective partnered with the City of London, Siemens and others to make recommendations about the future in order to help park owners make the most of the resources they have and to help developers of new parks make them as successful, inclusive and environmentally friendly as possible.

I will now show you a short film which summarises what we did, and would be very happy to discuss further. I have also offered to help colleagues and friends from Bosnia and Herzegovina, whether it’s in workshops or through an ongoing dialogue, to see if some of our experiences can help shape their future city making. So here’s the short film and I look forward to discussion afterwards.”